Non-topics

Summer Fiction: Honeybear, a Queer Adventure in Havana

Summer Fiction: 'Honeybear,' a Queer Adventure in Havana (Exclusive)

Read an exclusive excerpt from Murmur, Richard House's new novel.

July 27 2016 6:41 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Summer Fiction: Honeybear, a Queer Adventure in Havana

Read an exclusive excerpt from Murmur, Richard House's new novel.

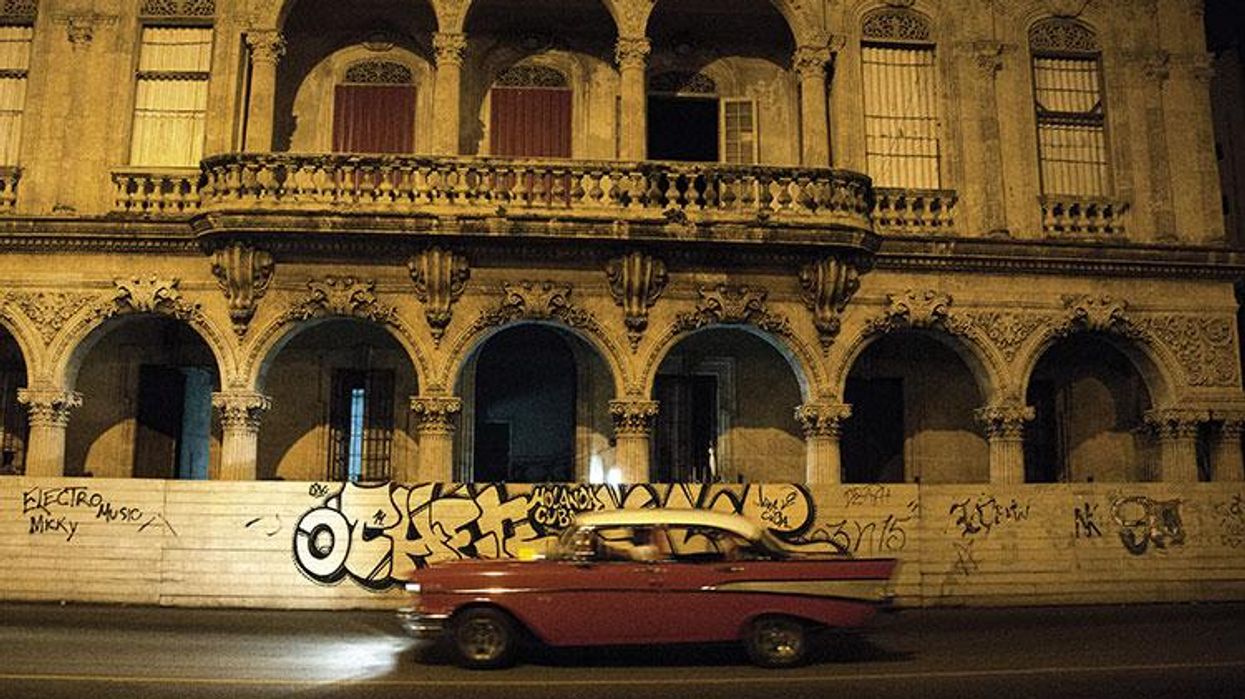

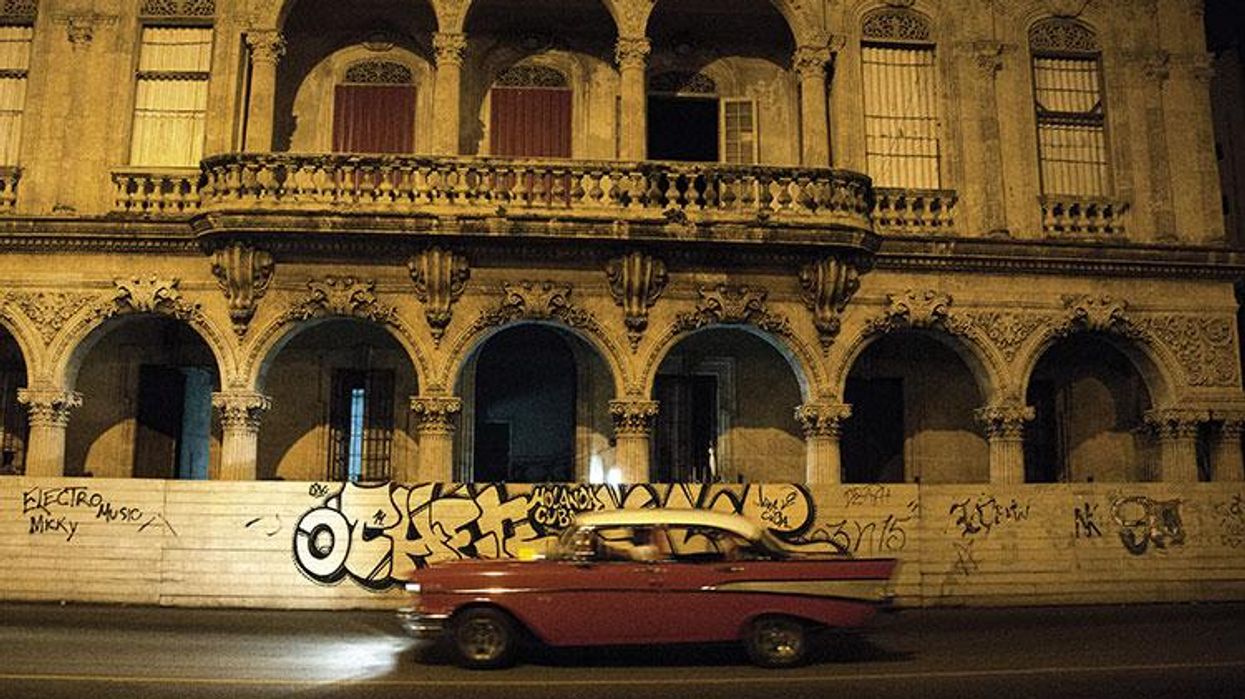

Photo: Catalina Martin — Chico / Cosmos / Redux (Havana).

Richard House is the author of three novels, including 2013's The Kills, which was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. His intricate, multilayered style involves writing myriad backstories for his characters that do not make it into the final novel but provide clues for dedicated readers looking for illumination. The story here is part of Murmur (to be published by Picador next year), which is about the start of an Anonymous-style protest movement called Monkey Williams. It's still in its early days, and its members Jonny and Han are attempting to rustle up funds to secure a series of actions they want to undertake, and at the same time discredit a fund called Bright Star.

Of House's current reading list, he says, "Sarah Schulman's interviews with former ACT UP members for the ACT UP Oral History Project is a phenomenal resource --we really need to know our history. Svetlana Alexievich's Seconhand Time is a social history of the Soviet Union during a period of collape and change through a Studs Terkel --like collection of voices. I've also been reading about the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI, who broke into the FBI offices in Media, Pa, on March 8, 1971, and stole every single one of its files. In my head these things connect --although I'm not sure I could properly explain why. We are living in strange times, so examples of personal courage (especially when people stand up against larger systems) and stories of mischief seen vital."

Read the excerpt below:

Both Han and Jonny appreciate the security guards in their military miniskirts and high heels. Bodes well, they agree. Such an arrival. The dour hall, the squeaky carousel, and these stern women in revolutionary green. Arrivals is lousy with tourists. They can’t get here fast enough. Han can’t help smiling as he hands over his passport. Already, he likes the country.

Fronted by a long lawn, the hotel cuts out a sizable section of the Malecón. There’s a swooping driveway with moonlike lanterns and boxwood trim. Yellow cabs queue for portage alongside pristine vintage cars. This is Spanish, as in American Spanish. The grand entrance, the tiled lobby, the staff in livery. Heavy beams and plank ceilings, vast lamps, and armchairs in which Europeans sit smoking Habanos and watch, disaffected, as the Americans arrive. It used to take a trek through Mexico to get here. How disappointing it must be to fly so easily now.In two days these trespassers will cruise to the Jardines del Rey.

A small sign in the lobby welcomes members of the Bright Star Fund.

As they check in, the clerk can’t help but look at Jonny and Han, from one to the other, and he insists on taking them to the room himself. He waits a little too long, even after Jonny has passed him a couple of dollars.

As grand as the room is, Han and Jonny have one bed between them. An air conditioner quivers and bumps like an aircraft. Han would rather sweat. Jonny checks that there is a safe. No problem. They can do this.

Hans asks which side. They’ve already shared a bed, but this announces the fact. Here they are. Havana. Grand hotel. Sharing a bed.

At breakfast Han takes note of the new arrivals. A young couple, honeymooners, he can’t place. The Boston Johnsons. The New York Hustons. The Houston Berkes. A flutter of alarm as they spot the Harrisons, associates of the Wildemanns, disembark from a golf cart along with the Entercotts. Wife, Sophie, ready for the sun. Husband, Paul, as is typical, on the phone. Unlike the other couples, they don’t pause to take it in but walk directly to the desk. They’re slumming it a little. Cuba isn’t St. Kitts. Sophie finds a seat and sits alone, crosses her legs, ignores the offer of spring water, the welcoming cocktail, and tilts her head back while the bags are stacked on a trolley. The spa staff wear linen Mao suits, white and blue. It’s no surprise that people from the fund know each other, this being an annual jaunt. One year a cruise, Kingston to Tulum. Another, a week in Italy. Florence, Rome, Naples.

The Entercotts acknowledge the Dohrmans and blank the Berrymans.

The game starts poolside. Jonny has already charmed the Entercotts. He brings them drinks, says he knows there is a staff for this, but they both look thirsty.

“Now you” — he eyes Paul — “look like a whisky-sour man, and you, I’m thinking mojito, but not so sweet, with cane sugar and soda.” (Jonny knows about the Entercotts’ taste for sours and mojitos from an interview in Metropolitan Home; Paul posed behind their patio bar, a repurposed Indonesian hardwood desserte.)

Sophie raises her hat with a delicate “Why, thank you,” delivered, for some reason, with a Southern slur.

He’s brought himself a bourbon and Han a Pink Fizz that has an umbrella and an orchard of orange and peach. Han mouths What the fuck? as Jonny places the stemmed glass at his side.

“I know you like them.” Jonny leans toward Sophie, confidential. “He once drank seven of these. After two he starts stealing things.”

Sophie sits upright, slow, as if her back aches, and scrunches her nose. “You don’t seriously like those?”

Jonny tells her it’s a punishment. “You know what he did this morning? He forgot the code for the safe. Twice.”

“Can’t remember numbers.” Han can’t sound anything but petulant.

“You set it.”

“And then I forgot.”

“Everything’s in there. Cash. Passports. Tickets. So he can only drink these all day. We had to call the front desk twice.”

This is true. Albeit deliberate. Jonny and Han waiting, arms folded, as the same clerk came to the room. After the second visit, the clerk set the number himself to one-one-one-one, told them to call him if they forget.

Paul picks up his drink and sits at the end of his wife’s lounger. The two are cozy together. He rests his hand on her knee. “Sophie’s the same. Absolutely useless with figures.”

“No! That’s unfair.”

“Absolutely terrible. Can’t remember phone numbers.”

“I’m just distracted.”

Han sympathizes. “Who remembers their own number?”

“Exactly! The solution is anniversary. Use it for everything.”

“Even at home?”

“Where else? Door code, safe. Everything else I keep in a book, which I always bring with me.”

“You hear that?” Jonny turns to Han. “Only don’t use ours. You never remember.”

“Do it backwards,” Sophie smiles as if this is crafty. “Instead of 1963, do 3691, then the month if you have to. No one will guess.” For some reason, she says, the backwards thing makes it easier to remember.

The perfect job would pass undetected. The family return home and find nothing wrong, nothing missing. No immediate alarm or panic, just that settling-in all travelers return to once the bags are unpacked, mail collected, pets returned, neighbors thanked. The usual usual. This would be Jonny’s preference. No one would know.

In reality, there’s no such thing. Something always gives the game away. However minimal. A lasting unnameable discomfort — a sense that you’ve come into the room at the wrong angle, that something isn’t right. At some deep unreasoned level you’ll always know.

They take a tour of Havana. Jonny, Han, and Paul, squeezed into the backseat of a cream Dodge Royal, Sophie half-turned in the front seat, a little buzzed on rum. Her smile is broader than the boulevard.

They haven’t done anything this spontaneous in years. They honestly haven’t.

He calls her “honey”; she calls him “bear.”

Jonny has a thirst that’s killing him. He wants a long cold beer. This temperature suits him fine.

To Jonny the city is municipal. Congress buildings, sports halls, squares for parades, parks for rallies. An outline of Che’s face scales a windowless high-rise. It’s all a little Soviet. The historic center, what they see, feels definitively postcardy. Outside of this it’s post-blitz or post-earthquake, with vacant lots, abandoned properties, decrepit buildings, apartments carelessly divided with breeze-blocks. Bikes on balconies, laundry, and ratty plants. A sense of rubble, of damage done. Concrete blackened with mold.

For Han the city presents itself in pieces, checkered entrances to hotels, grand facades. Motorbikes and beaten cars pridefully polished. You pass an intersection and see, fleetingly, a mid-street view of people at rest, at play, loosely grouped. His year in Cauco has been a tedious palette, impenetrable greens and blood-colored mud. This is so bright and various it’s intense.

The driver names places they should visit. “Havana is safe,” he tells Han. “We love every kind of people. Even Americans.”

Sophie thinks this is funny. Jonny has no idea what he’s talking about.

She wants to know if they are married, Jonny and Han. “You mentioned an anniversary. I hope you don’t mind me asking.” She’s curious. “How did you two meet?”

Han blinks. Jonny gives a — Sorry, what?

Sophie is off already. “It’s not like it means anything. Not these days. God.”

The assumption has its uses, but the ease at which the idea was raised irritates Jonny. He’s never had this assumption made of him, not once in his life. He wants to know, what exactly does she see? What?

The notion doesn’t trouble Han. Jonny and Han are always together by the pool, the bar, the restaurants. Everything confirms the thesis.

Jonny, unnoticed, unattended, takes the hotel key, a swipe card, from Sophie’s purse. When they return to the hotel they leave the Entercotts searching pockets, certain that the card has to be somewhere.

Jonny and Han regroup pre-dinner at the Cabana Bar. The clerk who checked them in serves them drinks, tells Han he has a nice watch, holds his wrist as he looks it over. Asks if he’s had a nice day.

They find loungers beside the honeymooners, who have set out towels and bags to define a private area. When Jonny asks if they mind, the man turns his back without answering.

Han holds up his drink and peers through the mess of mint, bruised lime, all that honey-colored rum, and slurs the horizon. That pretty view, glassy, sun-sparked, is all about slaves and sugar. Never forget. He can still feel the man’s imprint on his wrist.

Jonny warns Han that they’re working the second tier. Remember, these aren’t A-listers. “The man beside them,” he says, “his wallet is in that bag. I’ll make a distraction. Get the wallet and copy the details from the debit card. Make sure it’s his debit card.”

Han takes a sneaky look. There’s a soft bag beside the man’s lounger, slightly open. He can see keys, a swipe card, a paperback novel, a black wallet.

Sophie joins them, spritely after a late session at the spa. “So he’s let you off those awful pink things?”

Han raises his glass to toast her. “It’s Havana. You have to drink rum.”

As they chat, the Newly-wed Husband holds forth about the failure of the Cuban Revolution, how the country is backward because of the embargo, and how you really don’t want to know about the lives of the people serving you — you pack extra toiletries, toothpaste, sanitary pads, over-the-counter medications, treats, and gifts, because you’ve read on Trip Advisor that this is what you ought to do. It’s Cuba. Bring spare clothes, leave anything you don’t need and anything that can be traded. These people aren’t even allowed passports. Newly-wed Husband emits a sourness, an undisguised can you believe this. If he could hit a button to make everybody disappear, his hand would bleed from punching it.

Sophie calls him “an odd one” and tells them confidentially: “at the last Bright Star event we were asked to introduce ourselves through our spirit animal. The prize was something nice, like a private tour. The Seattle Stevens introduced themselves as snow foxes, but he” — she signals to the Newly-wed Husband — “when called to the microphone said, ‘Tonight I’m an airborne virus.’ ”

Newly-wed Wife becomes quiet when she notices Jonny watching her husband.

Sophie stands up and scans the loungers. “I said I’d meet Paul an hour ago. Haven’t seen him, have you? I hope he’s having a good time. You can never tell.”

Newly-wed Wife now whispers to her husband. The man turns about, ready to confront Jonny. Slathered in protective cream, the couple appears a little orange and shiny, as if preserved.

The man leans close and asks Jonny if he has a problem.

Jonny similarly leans in and tells him, nice and quiet, “You’re not my type.” This should be done, but Jonny wants to scratch. “By the way, there’s something on your breath.”

Newly-wed Husband automatically wipes his mouth.

“I said breath” — and then with care, first clearing his throat, Jonny tells the man that his breath stinks of cock.

The man’s head pops back. What did you say?

Jonny leans closer still. “Cock. Your breath stinks of cock. Something awful.”

The response is more explosive than Jonny could have hoped. Newly-wed Husband’s fist lands him square in the chest. Jonny, knocked off balance, sends his drink over other guests and cracks his head on the decking.

Back in their room, Jonny has Han check his head and then the bruise. His neck is jarred, and he can’t move his right arm high enough, so Han has to unbutton his shirt. Across his chest is a livid bruise. Han tells him it isn’t so bad, although, impressively, it looks like a map of Cuba.

Jonny stands in front of the mirror and says he wouldn’t know. “You got the wallet?”

Han has the details. The debit card, the credit cards, the American Express (and who uses those these days?). Afterward he dropped the wallet and the novel into the pool.

The bruise looks like a wine stain, but mostly like a map. Han points out Havana, Bay of Pigs. And there, pointing at Jonny’s nipple, Guantánamo Bay.

Han sits with the Entercotts at supper. The Newly-weds’ table is empty. Complimentary wine is brought to their table, a basket of fruit to their room with tokens for spa treatments. Sophie asks if Jonny is all right, and Han admits there’s an actual bump on the back of his head. He’s never seen a man punched before.

The clerk who asked after his watch supervises service for their table.

Jonny takes the service stairs to the Entercotts’ floor. He uses Sophie’s swipe card to enter the suite and once inside goes directly to the wardrobe and the small metal safe. Their bedclothes are disturbed. A perfume bottle sits at the very edge of the dresser, and the room holds a heavy scent, sweet and floral. Jonny resists setting the bottle further back. Sophie is the kind of person who, once dressed, hair fixed, would spray scent into the air and walk through the descending mist, eyes closed.

Jonny kneels beside the safe. Three-six-nine-one — the door loosens and opens, and there are their passports, a watch, an envelope of money, a docket of papers. Beneath these he finds Sophie’s notebook, a black moleskine stuffed with notes, receipts, and several photographs. The photographs, images printed onto plain paper, two to a page, are folded; the colors seep toward orange, the shadows diluted. In one a younger Sophie and Paul stand at either side of a boy, a teenager in cricket whites who sits in a chair, his arms curved inward, his body a little crooked, small, perhaps under-formed. Sophie’s smile sticks hard-edged, effortful. The boy looks like her, handsome, the same oval face and strong forehead, the same fine thin nose. His mouth is open, his eyes upturned to look unfocused past his father. Unlike his parents, he shows no awareness of the camera. Behind them is the edge of a garden, spiky cordylines, then whitewashed walls and sash windows of what Jonny takes to be an institution.

He searches through the notebook for numbers, accounts, addresses. Looks again at the photograph.

The preparations are now in place. They can use the money from the Newly-weds’ credit cards for the flights. They know the safe codes for the Entercotts and their address. In two days they will fly to New York; by the weekend they will return to Cuba and rejoin the Bright Star tour.

About a month after the Entercotts return home, things will start to go wrong. Money will go missing from their accounts, services will be cut, bills will be unpaid. A disruption not only to their lives but to their reputation.

Jonny returns the notebook to the safe. He winces as he stands and asks himself, Why did I do that? He looks again at the photograph.

The thing is not to think of them as people. The Entercotts. Not people who grieve or love or suffer.

The perfume, less sweet now, robs his breath.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of OUT. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.