Thomas Kurmeier/Getty Images

Last Call Chicago documents the role gay bars — and played in the local LGBTQ+ community.

January 20 2023 4:00 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Last Call Chicago documents the role gay bars — and played in the local LGBTQ+ community.

Members and allies of Chicago’s LGBTQ+ community have an invaluable resource in Last Call Chicago: A History of 1001 LGBTQ-Friendly Taverns, Haunts & Hangouts, a book by journalists Rick Karlin and St. Sukie de la Croix. It documents personal stories from those who found refuge and community within these businesses, many of which closed decades ago.

“So much of our life is in the bars, and that’s where so much gay history took place,” Karlin recently told our sister publication, The Advocate. “Before there were organizations, any kind of planning took place in the bars. So it’s really important to document that history.”

Karlin was the entertainment editor at various Chicago publications for 25 years, and de la Croix wrote a column called Chicago Whispers (and a book of the same name) where he’d interview LGBTQ+ people about experiences as far back as the 1920s and ’30s.

“I’d interviewed about 500 people, just about their lives in Chicago,” de la Croix explained. “The bars cropped up a lot, because the bars back then were the community centers.”

A lot of the book’s charm comes from funny stories from bar owners and regular customers, written in the style of Karlin’s gossip columns going back to 1978. Karlin explained he would take information from bar advertisement or flyers, “and I’d make some funny way to make it into kind of a gossipy thing. ‘If you’re really broke, head over to Berlin on Thursday night, where they have 75-cent drinks and a dollar cover. Helen Highwater was seen there opening her purse for the first time.’ I’d make up these characters and I’d write about them.”

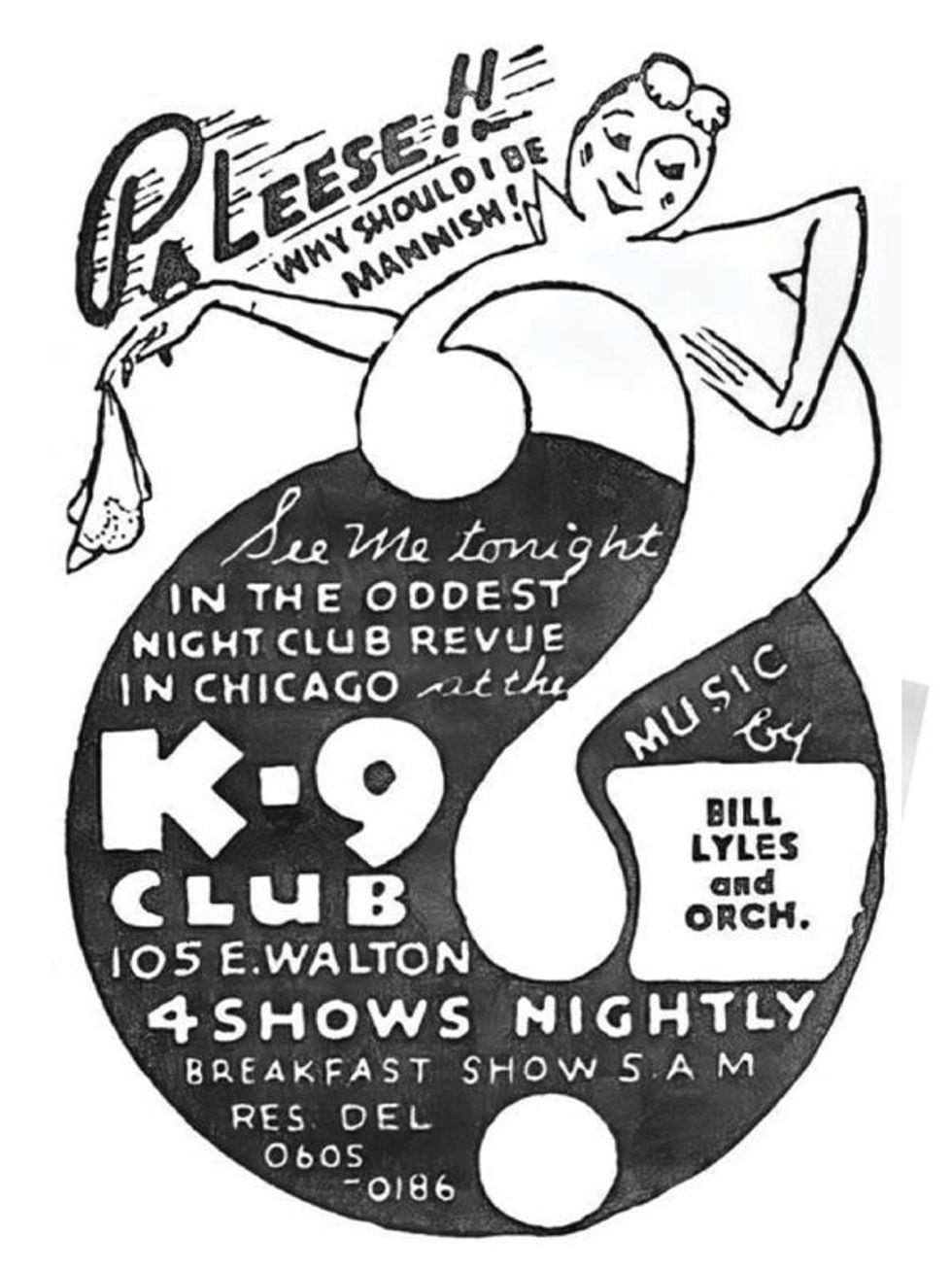

To cover pre-Stonewall establishments, de la Croix had to do some additional digging through newspaper archives. “I interviewed a man in his 90s, and he…told me that he snuck into a speakeasy during Prohibition and saw a drag show.” De la Croix said he knew, “when Prohibition ended, the next day all these clubs opened overnight,” so he searched papers from the time and found advertisements for a bar of the same name, the K9 Club.

Many of the Prohibition-era businesses were also documented through press coverage of police raids and arrests for public indecency. One was called the Green Mask Tearoom, located in the basement of a brothel. It was owned by chorus girl and burlesque performer Agnes “Bunny” Weiner and her lover Beryl Boughton, a silent movie actress.

Boughton “was in a cowboy movie,” de la Croix recalled, “and she had to be in a sandstorm and it took a lot of her face off. She sued and won a lot of money, and they opened this lesbian cafe. I looked back in the newspapers and found that they’d been raided many times.”

One of the reasons Chicago has such a unique LGBTQ+ history is that the city’s bar culture is different from other big cities. “When I was growing up here, it was not unusual for every block to have a bar on it,” Karlin said. “It was a very blue-collar, beer-centric town.”

Until recently, a quirk of the city’s liquor laws meant that licenses were connected to an address, rather than the owner of the bar. “If you had a liquor license and you wanted to move your business three doors away, you couldn’t do that — but you could let your liquor license be used by somebody else in your space. So what happened is when people got tired of running their business or they ran out of money or whatever, they just let somebody else open a bar in their same address.” That led to a number of locations that were home to a series of gay bars and clubs over the years.

“Illinois was the first state to decriminalize homosexuality, in 1961,” de la Croix said. “All the obvious homosexuals in the Midwest living in small towns, drag queens and things, they all thought, ‘This is great,’ so they all moved to Chicago.”

“The other thing I think that helped is a weird thing to say, but the Mafia owned all the bars, and the cops took money from them,” de la Croix explained. “That corruption actually gave gay people a space in Chicago.”

“Even when the cops would raid the bars, the bars would know ahead of time,” Karlin added. “They would phone first to say they were raiding the bar, so they would get people out. My father was a Chicago cop, and we found out that he was one of the cops that was not only raiding the bars but on the take from the bars.”

As cultural and political changes came to the city, the local bar scene changed too, providing important meeting places for community and activism.

“In the ’60s when women’s liberation started in Chicago, women were sick of going to these Mafia bars,” de la Croix pointed out. “So women started their own coffee shops. And then when AIDS came along, you knew about AIDS because there were all these fundraisers in the bars.”

In recent years, the LGBTQ+ community’s relationship with bar culture has changed again, with younger generations using online spaces to connect and feeling less tied to specific neighborhoods or businesses.

“Young people don’t go to gay bars as much anymore,” Karlin said. “They just go to any bar they want…which is what we fought for all those years — that gay people could go anywhere and be accepted anywhere. Unfortunately, now it’s biting the gay business community in the ass, because people don’t feel as much of a need to go to gay bars. Between that and…going out cruising is not what you do anymore. You do it on your apps.”

“In Chicago, the bar owners tend to be really invested in the community,” Karlin said. “Art [Johnston] who owns Sidetrack, the most popular bar in Chicago, would give tons of money back to various causes. They basically...I wouldn’t say blackmailed, but strongly encouraged liquor companies to become active and donate money. If they don’t, they don’t carry them in their bar.”

Now, as bars and restaurants across the country attempt to recover from the pandemic, Chicago’s queer bar scene has decades of resilience to fall back on.

“I think in Chicago there will always be a gay entertainment district,” Karlin said. Gay bar owners, “learned their lesson early on and started buying the properties when they moved into what is now known as the Halsted area and Andersonville. So, they don’t get priced out as much.” In the end he says gay bars will survive only “if they keep up with what the people are looking for.”

This is a shortened version of a piece that initially ran in our sister publication, The Advocate. Read the original here.